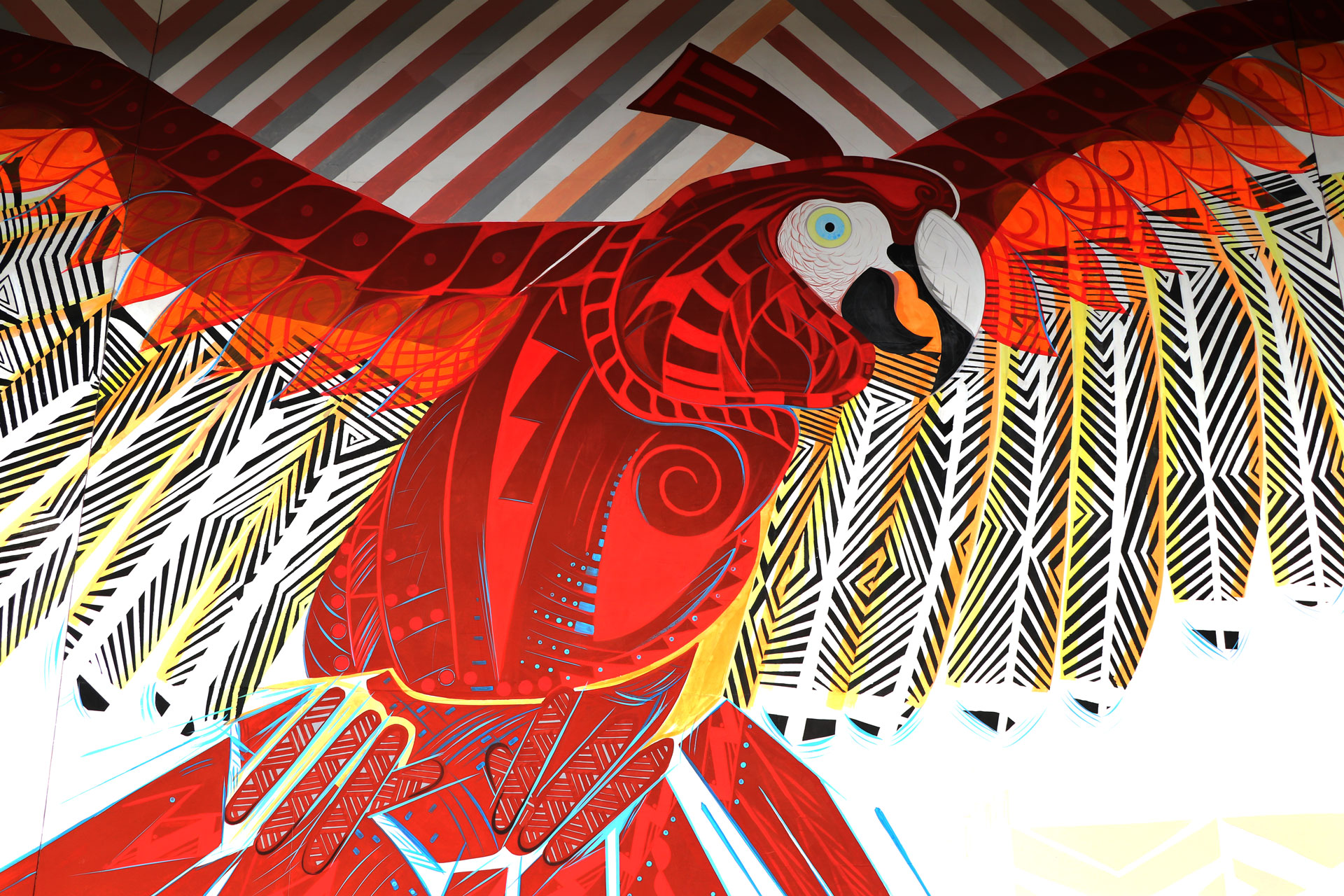

The sky was bright and restless, a royal blue canopy unfurled between the horizons like a vast imperial banner. Dedicated to the deified sun at its midday zenith – an aspect of solar energy embodied by a giant fiery macaw called Kinich Kakmó – the crumbling Mayan pyramid beneath my feet was overgrown with parched grass and flowers, wiry shrubs and shady trees.

Below, the soporific city of Izamal was sprawled with its grid of cobblestone streets and alleyways, grandiose colonial churches, plazas, and townhouses, all painted a blazing sunflower yellow. Clambering to the summit where once sacrificial offerings were laid, I paused to reflect on the phenomena of syncretism, the mysteries of the pre-Columbian universe, the Mayan concept of time, and the destruction of worlds.

Dividing the Caribbean Sea from the Gulf of Mexico, the Yucatán peninsula has been the stage for numerous apocalyptic dramas, beginning 66 million years ago when it was struck by the giant meteor that is believed to have wiped out the dinosaurs. Beyond the cataclysm of ash and fire, mammals survived and flourished, and at the end of the last Ice Age, humans arrived in the Americas.

Today, the Yucatán’s sprawl of jungle-shrouded palaces and abandoned acropolises recall a succession of luminous civilisations, commencing in 2000 BC when the first Mayans laid the foundations of pyramids. But from the 16th century, Yucatán was a point of first contact for early European explorers, and thereafter, the birthplace of Mexico’s first Mestizo child.

The conquest brought persecution, not least from the Catholic church. In Izamal, visible from the pyramid of Kinich Kakmó, the Franciscan monastery complex boasts the second largest atrium in the world after the Vatican, and was once the residence of the notorious Diego de Landa who, in a single day of fervour, obliterated thousands of Mayan artefacts. “Works of the Devil,” he raged. “I burned them all ….”

But the conquest was neither complete nor entirely successful. Today, on the streets of Izamal, Yucatec Maya is as widely spoken as Spanish, and throughout the peninsula’s network of stoic villages, the belief persists that Mayan civilisation will one day flower again.

Just as the pyramid of Kinich Kakmó was too gargantuan to dismantle, the fiery macaw it exalts is simply too vivid and enduring to die.

Source: The Independent