There was no breeze or cloud cover, only the clasping heat of the sun and the light percussion of crickets to punctuate the fervent speeches and fighting talk. A chorus of cicadas click, click, clicked into life, before whirring, klaxon-like, in violent high-pitched unison.

“The people are reclaiming the Tabasará river as their historic patrimony,” declared Ítalo Jiménez, the fierce and wiry President of M10, a 500-strong protest group otherwise known as the April 10th Movement for the Defence of the Tabasará River.

“The river is our life. It can never be dammed. If the government wants blood, they’ll get blood. We’re ready.”

It was almost noon on 6 May 2011 and just under one hundred members of M10 had gathered at the steel bridge over the Tabasará river in western Panama – to fight.

Coursing through the mountainous province of Chiriquí, the Tabasará is one of the longest and most beautiful rivers in the country and an on-going point of conflict between indigenous communities and energy firms. For over three decades, a variety of hydroelectric projects have been threatening the area.

First came Tabasará I – a gargantuan 220 megawatt dam designed to supply energy to the controversial Cerro Colorado copper mine. Slated for construction in the 1970s, President Omar Torrijos was forced to scrap it after widespread opposition.

In the late 1990s, a scaled-down 48 megawatt version of the project was proposed. It too sparked heated protests, culminating in the arrest and incarceration of several indigenous activists on 10 April 1999.

In commemoration of that day, the April 10th Movement was born, and after years of contention and protracted legal battles, the group emerged victorious and Tabasará I was shelved.

Today, a new threat to the river comes from the Barro Blanco hydroelectric scheme- a 29 megawatt dam promoted by the Panama-registered company Generadora del Istmo S.A (GENISA). It is proving just as unpopular and insensitive as its predecessors.

If left unchallenged, Barro Blanco will flood hundreds of hectares of land belonging to the Comarca Ngobe-Buglé – a semi-autonomous reservation owned and administered by Panama’s indigenous Ngobe and Buglé peoples.

Specifically, scores of communities along the riverbanks will be displaced and the lives of some 5000 Ngobe farmers who rely on the river for potable water, agriculture and fishing will be negatively and irrevocably impacted.

It was almost noon On 6 May 2011 and M10 had decided to take action – they were going to blockade the international Panamerican Highway, Panama’s principle artery.

“This ends here, today,” said Ítalo.

Hauling branches, boulders, bricks and stones into make-shift blockades, M10 sealed the highway against on-coming traffic. One by one, they unfurled their banners and raised their flags.

A long queue of vehicles began to form on either side of the bridge and rumours began circulating of an imminent clash with the national police, who enjoy a notorious reputation for their heavy-handed put-downs.

But the decision had been taken. There was no going back.

The Art of Denial

Twenty-four hours earlier I’d explored the Tabasará basin with the help of a local activist, Oscar Sogandares, who works closely with M10 and publishes the Asociación Ambientalista de Chiriquí (ASAMCHI) environmental blog.

As we drank coffee with Ítalo at his house in Nuevo Palomar, we talked about Barro Blanco and its ill-prepared Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), submitted in 2008 and according to Panamanian law, now out of date.

At worst, said Ítalo, the EIA contained completely falsified information. At best, it represented facts selectively.

Among several serious omissions was a complete failure to disclose the true situation regarding the indigenous people living on or near the banks of the river (including those who would be indirectly affected by the diminished supply of potable water).

Maps accompanying the assessment, for example, failed to show the existence of several Ngobe communities on the Tabasará.

For years now, indigenous rights have been enshrined by Convention 169 of the International Labour Organization and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. In the latter, article 32 asserts:

‘States shall consult and co-operate in good faith with the indigenous peoples… in order to obtain their free and informed consent prior to the approval of any project affecting their lands or territories and other resources, particularly in connection with the development, utilization or exploitation of mineral, water or other resources…’

This legal stipulation – and several others like it – are echoed by Panama’s Law 10, which guarantees Comarca land as inalienable:

Indigenous communities ‘can only be transferred from their regions and reserves, or the land which they own, by means of previous consent.’

And yet in March 2011, construction work on Barro Blanco commenced without any prior consent, or indeed, official consultation with the affected communities.

“There is no negotiated agreement,” said Ítalo. “There is no agreement whatsoever.”

According to ANAM, Panama’s environmental agency, GENISA conducted its public consultations in a proper fashion on 8 February 2008 during a public meeting in Tolé – a non-indigenous town located in eastern Chiriquí, several kilometres outside the Comarca.

M10 says they were not informed about the consultation, which was publicized with a flyer drop that reached the residents of Tolé, but somewhat mysteriously, no-one else.

By chance, an old Ngobe woman found one of the flyers in the street and took it back to her village. This was the first time anyone in the Comarca had heard anything about Barro Blanco and M10 immediately gathered a 50-person contingent to travel to Tolé.

When they arrived at the meeting hall, they were barred from entering, and therefore, from posing any questions to GENISA. When finally they broke inside, the company announced that it was not holding a public consultation, but rather a private meeting.

Despite this, ANAM regards the meeting as sufficient public consultation for the project to advance. Apparently, GENISA and the Government of Panama feel that wilful denial of reality is enough to make it magically disappear.

But GENISA’s peculiar difficulty in addressing the concerns of the Tabasará communities is sadly echoed by the Asociación Española de Normalización y Certificación (AENOR) – the organisation responsible for assessing GENISA’s application for carbon credit awards.

Despite a first-hand visit to the area and two rounds of validation during which M10 submitted complaints, AENOR made the following astonishing claim in their final report:

“The validation team can conclude that the most relevant communities involved in the area of the project were consulted [and] all of them supported the project activity…”

One begins to wonder whether GENISA and AENOR’s pathological denial results from profound incompetence or something entirely more venal.

According to M10, Barro Blanco is so fraught with abuses, inconsistencies and illegalities, it should have been suspended years ago. One thing is certain, AENOR has not learned from its past mistakes.

According to James Anaya, the UN’s Special Rapporteur for Indigenous peoples, AENOR completely failed to recognise the indigenous population living in the shadow of the Chan-75 hydroelectric project in Bocas del Toro province.

At the time, Ngobe protesters reported intimidation, threats, violence, torture and sexual assault at the hands of state security and other hired thugs. An international order suspending the project was issued, but this was completely ignored and construction continued unhindered.

Amnesty International recently reported on the despicable and shameful conclusion to Chan 75, saying that the Government of Panama now appears to be flooding Ngobe lands despite the fact that they have not been fully evacuated.

“The Government of Panama and the companies they support have zero respect for indigenous people.” Said Oscar. “Panama’s indigenous people have a huge struggle ahead of them.”

As for GENISA, it does appear that they can be shamed into submission if sufficiently threatened with negative exposure. In October 2010, the company withdrew their loan application with the European Investment Bank (EIB) just one week before a scheduled fact-finding visit.

Tellingly, the EIB had been responding to complaints that Barro Blanco contravened their due diligence guidelines.

Today, the question remains whether two other potential backers – The FMO, the entrepreneurial Development Bank of the Netherlands, and the DEG, the private finance arm of the German KfW Banking Group – will listen to the cries of protest sounding from the banks of the Tabasará river.

Land and People, One Single Inseparable Reality

Few roads or highways penetrate the sparsely settled Comarca Ngobe-Buglé – one of the most remote and entrancing regions in Central America. Instead, internal travel is conducted via a network of copper-coloured mule trails, all threaded tirelessly over the hills and valleys.

It was a hazy morning when me and Oscar set out to explore the Tabasará river basin. Heavy storms had recently awoken the earth with a flush of deep green foliage, but the full deluge of winter had yet to commence. The air was damp and tangy and smelt strongly of wet grass and clotted mud.

Heading south with our stoic horses, we skirted the river on its long meander toward the ocean. Now and then we’d pause so Oscar could explain the dynamics of the conflict in more detail, or point out some feature of the landscape, a particular tree, plant or animal.

Descending to a moist gully filled with lavish ferns and babbling springs, he lifted some foliage to reveal a dazzling blue frog hidden in the shadows, glowing like neon light.

“The gallery forests along the banks of the river are a highway for many different species,” said Oscar. “Species like this blue morph poison dart frog, which is endemic to the region, and the critically endangered Tabasará rain frog, also endemic. Both will face extinction if the dam is constructed.”

We watched for a moment as the frog perched motionless, then without warning, leapt away into a mass of tangled plants.

“The river itself is a migration route for diadromous fish.” Continued Oscar. “They spend their life-cycle in the salt-water marshes on the coast and then migrate upstream to the head-waters. Unless they can adapt and find an alternative course, they too will die out.”

Departing the gulley, we rose and fell over a series of ridges, emerging here and there to expansive vistas. Trails of mist clung ghost-like to the hills and a lone hawk traced the sky above jagged fields of sugar cane.

Soon we rejoined the Tabasará at a long, low suspension bridge. Beneath us, the water swirled and rumbled over a bed of weathered boulders.

“The rapids are what keeps the water alive.” Said Oscar. “They’re what maintains the oxygen in the water. Once the water is flooded and it becomes stagnated, it loses oxygen, fish die, native fauna die and the water quality drops down. And that’s what we’re fighting against.”

Crossing the river, we soon arrived at a small Ngobe community perched on the banks. A scattering of cane-and-thatch houses encircled a grassy clearing where children gathered green mangos and wild flowers. The aroma of sweet, stewed coffee and smouldering wood permeated the air.

Inside an open-air school house, a group of women nursed babies and talked quietly. Their brightly coloured dresses were adorned with triangles and zig-zags symbolising the rugged mountains and rivers of their homeland.

“Mother earth is the first mother.” They told us, as we ate a simple lunch of rice and beans. “She is the first owner, everything comes from her.”

Like many indigenous people, the Ngobe have a rich and intimate relationship with the natural world. Their survival directly depends on the cultivation of yucca, maize, beans, plantain and other staples, whilst scores of different plants are used in traditional medicine, craftwork and construction.

“We want a good life here by the river,” they continued. “A true life, teaching our language in our school.”

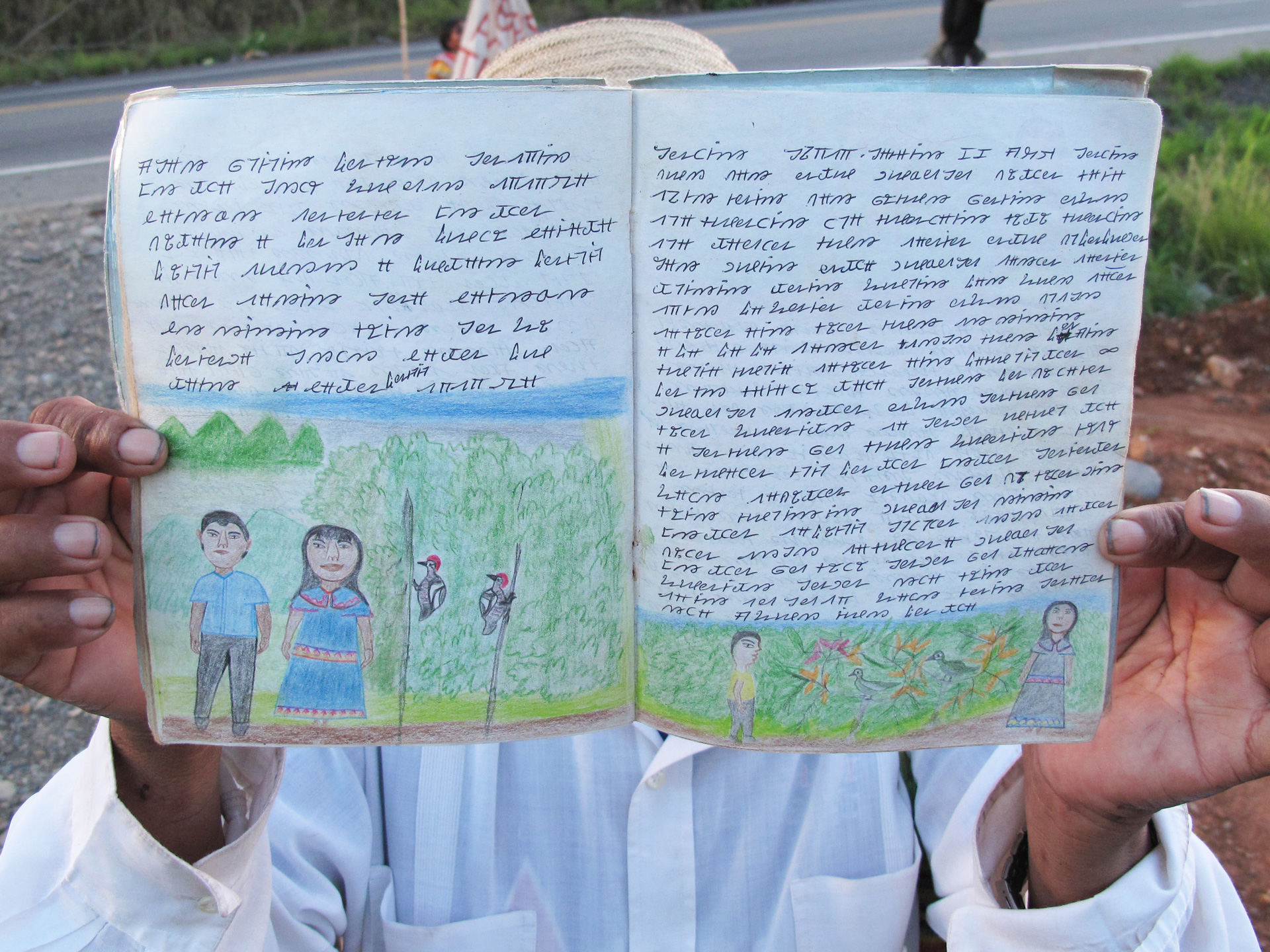

A young boy called me to the blackboard to demonstrate the writing of his ancient language, Ngabere. In a world of rapidly diminishing diversity, Ngobe culture has never seemed so important – or so fragile.

“Quebrada Kia,” he said with pride, pointing to the chalk glyphs he’d written. Quebrada Kia – the name of his community…

Action speaks louder than words

It was twenty-four hours before M10’s confrontational blockade of the Panamerican highway and the group had convened at their camp to discuss strategy.

Beyond a haphazard tangle of string hammocks and make-shift shelters, a furrowed dirt-road led to the partially razed banks of the Tabasará river.

For over a month, the group had been diligently stationed outside the project site, preventing diggers from refuelling and bringing work to a standstill. Quietly victorious, M10’s red and black battle flag rippled in the afternoon breeze, but the situation was quickly changing.

“Now we have no choice,” said Manolo Miranda, an M10 leader and spokesperson. “The commission has failed. Dialogue has failed. Now we’re talking about the highway – and the protests must be indefinite…”

A few days earlier, M10 had participated in a tripartite commission aimed at reaching a consensus with GENISA, and if possible, a signed accord.

On 4 May 2011, the committee – unevenly composed of one-part M10, one part ANAM and one part GENISA – had assembled in an open-air meeting hall in Tolé, closely observed by Ngobe community members, journalists, environmentalists and townspeople.

The talks were chaired by Vice-Minister Luis Carles and there was an air of orchestrated theatre throughout the proceedings:

A primary school teacher made an emotive plea for ‘progress’.

A chief engineer sobbed that his rights had been violated.

And Carles himself admonished M10 with much sweaty gesticulation, placing the responsibility of ‘a solution’ solely and squarely at their feet.

Numerous arguments in favour of the dam were put forward, including the oft-repeated and largely deceptive claim about Panama’s ‘growing energy needs’.

In truth, Panama’s energy demands can be met by current supplies for many years to come. The country actually enjoys a healthy surplus which it exports to places like Mexico, which have been experiencing short-falls ever since the 1994 North American Free Trade agreement came into force.

The principle argument in favour of the Barro Blanco dam, therefore, is an economic one. According to GENISA, the project will create 300 temporary jobs and 25 permanent ones. In Tolé, a non-indigenous town with high unemployment, the argument resonates positively.

But for the Ngobe who rely on the Tabasará for food and potable water, short-term jobs are hardly a fair trade for their resources. If properly managed, the river has the potential to sustain their communities indefinitely, generation after generation, long beyond any speculative term of employment.

Incidentally, it should be noted that Panama’s labour laws tend to discourage employers from recruiting individuals for longer than a few months at a time, and that none of the 25 permanent positions are likely to be sourced locally – those can only be filled by skilled technicians.

The nebulous cry for ‘progress and development’ – invariably accompanied by promises of a new school, health centre, roads, electricity or some other civic amenity – is also unconvincing, mainly for reasons of historical exclusion.

The Ngobe, who are sometimes called Panama’s ‘forgotten people’, are one of the most impoverished and underprivileged groups in the Americas. They survive in sparse, isolated communities with little outside intrusion and next to no modern technology.

Centuries of abuse from the non-indigenous majority has made them intensely self-reliant and fiercely independent. They enjoy their own language, religion, beliefs, customs and rituals, and they work hard to preserve their culture.

As one Ngobe speaker put it to GENISA:

“Our ancestors didn’t need electricity and neither do we. Development? We want our own development, not yours.”

The tripartite commission ended as it was always bound to end, thoroughly deflated and with no final accord.

The Storm on the Highway

The tarmac shimmered listlessly in the midday sun. There was no relief, only the deep monotony of tropical heat and a grinding determination to see things through. M10 were seeking nothing less than the complete closure of Barro Blanco and they would stay on the highway to the end.

But soon the pressure began to mount. Hour by hour, degree by sweltering degree, entrenched at the bridge over the Tabasará, a series of minor dramas unfolded:

Journalists sought out interviews.

Government communiques came and went.

Stranded motorists vented their fury.

Spiritual leaders prayed.

And rumours continued to circulate of an impending police repression.

But M10 were no strangers to protest, or indeed, clashes with the authorities.

In February 2011, the government of Panama hastily passed a new bill liberalising the nation’s mining laws. Known as Law 8, the new legislation directly and gravely concerned the Comarca Ngobe-Buglé, which is home to one of the world’s largest copper reserves.

Specifically, Law 8 provided foreign companies bold new rights of exploitation and acquisition, and when petitions against it were ignored, the Ngobe co-ordinated a series of high-profile protests, closing the Panamerican Highway at several points.

The conflict lasted several days and involved several thousand protesters, including the ranks of M10 and other grassroots indigenous and campesino movements. When political manoeuvres to divide the Ngobe failed, the government finally admitted defeat and repealed Law 8.

Throughout the ordeal, skirmishes with the police had resulted in numerous injuries, but no deaths. Several months earlier, protesters in the city of Changuinola had not been so lucky. Opposing Law 30 had cost several protesters their lives and dozens more their eye-sight.

Back at M10’s blockade, the afternoon heat refused to dissipate. The air was thick and smelt of rich, wet earth. The sky swam with vapour and negatively-charged ions.

It was nearly five o’clock and heavy storm clouds had engulfed the hump-backed hills. They were bruised and swollen and threatening rain, but stubbornly refused to break.

Suddenly, word arrived that armed riot squads were amassing a few kilometres from the protest. Everyone scrambled to action, gathering rocks and sling-shots and other impromptu weapons. Battle fires were lit, sending thin white plumes into the sky.

Children and journalists were ushered to a safe distance and I watched as a local priest, Padre Narciso, mediated desperately between M10 and a police commander who had arrived on the scene.

Beyond the densely packed crowd, through a thin bank of trees on the edge of the highway, dark squads were assembling with shot-guns, batons and body-armour. Time slowed to a painful crawl. Minute after minute, second after second, the clouds rumbled, the sky crackled.

Still it refused to rain.

The Commander came and went. The squads readied their gas masks. And then out of nowhere, without warning, a lorry thundered across the road… then a second… a third… a fourth.

The highway was open, we were told, and M10 had won. During last minute telephone negotiations, Government Minister Roxana Mendez had agreed a provisional suspension of Barro Blanco. The struggle was over.

A stream of vehicles crawled past the protestors – buses, cars, vans, trucks – engines roaring and horns sounding. And then, more ominously, a rumbling procession of diggers and bulldozers. One by one, spots of rain began to fall on the tarmac. First a light shower, and then more refreshingly, a deluge…

Broken Promises

On 7 May 2011, twenty-four hours after the protests, the government and M10 convened in the city of David to sign a tentative peace accord. Minster Roxana Mendez, represented by Vice-Minister Carles, officially guaranteed Barro Blanco’s ‘immediate suspension until the necessary studies are done’.

It took the Government of Panama just 10 days to break its promises. On 17 May 2011, during another round of negotiations in David, Vice-Minister Carles staged a flamboyant and apparently pre-rehearsed walk-out.

Riot police – primed and ready – moved into position on the Tabasará, seizing control of the bridge and project site, which had already been abandoned by the protesters as part of their accord.

In the nearby town of Tolé, dozens more police arrived and erected encampments where they have been lodging ever since. They appear to be engaged in on-going military-style training exercise complete with early morning drills and verbal abuse.

Predictably, construction work on Barro Blanco resumed right away. Further downstream, work on a different hydroelectric project, Tabasará II, also began simultaneously, compounding M10’s desperation.

Now that GENISA enjoys the 24-hour protection of state-sponsored thugs, the group fears ugly scenes like those witnessed at Chan-75 – a site which was ‘militarised’ by the police in an identical fashion.

But if M10 fail to defeat the project, they stand to lose everything.

A particularly grave concern is that once Barro Blanco is completed, nothing will be able stop developers extending the dam walls from 103m to 160m, thus converting the plant into the 220 mega-watt monster originally envisioned by the 1970s architects of Tabasará I.

Few options are open to the group.

Drect action might force attention on the issue, but it carries the likelihood of violent repression, and with repeated closures of the public highway, diminished public support.

International institutions such as the UN and Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) offer hope of legal intervention, but litigation is often complex and time-consuming, and as experience shows, President Martinelli is hardly known for compliance or fair play.

The President’s own role in instigating human rights violations appears to be considerable.

Displaying admirable diplomatic restraint, US Ambassador to Panama, Barbara Stephenson, noted Martinelli’s ‘autocratic tendencies’ in a confidential embassy cable in August 2009:

“Martinelli may be willing to set aside the rule of law in order to achieve his political and developmental goals,” she said.

In fact, President Martinelli – who famously owns Panama’s fourth best supermarket chain – has so consistently trampled on human and indigenous rights, it would appear that the country has a boardroom thug for a President, not a world-class leader.

Meanwhile, the environmental costs of his ‘supermarket sweep’ are being flatly ignored by a self-serving political class who appear to know the cost of everything and the value of nothing.

Panama’s grandiose energy expansion plan, for example, includes over 160 hydroelectric projects – more than can be found in all the countries of Central America combined. Whilst conforming to the soaring neo-liberal spirit of the Plan Puebla Panama (PPP), it is simply too much for a country the size of Panama, which is now in danger of desertification.

Thus the struggle for the Tabasará is a key flash-point in a much greater struggle for the future of Panama, its resources, its environment, its rural poor and its indigenous peoples.

If Martinelli and his cronies succeed in their grotesque scramble to sell-out the country, not only will Panama have lost itself forever, the world will have lost a vital bastion of ethnic and biological diversity. The war for the Tabasará river – as minor and provincial as it might seem – is far too important to lose.

Source: Intercontinental Cry